Vacation rental managers compare themselves constantly.

To competitors.

To “the market.”

To what their PMS, OTA, or revenue tool says is “average.”

To what their team reports in monthly reviews.

And yet, most of the time, the comparison itself is flawed — not because the data is wrong, but because the market being used as a reference is poorly defined.

When managers say:

- “We’re underperforming the market,”

- “Our ADR is below average,”

- “Occupancy is weaker than competitors,”

the real question should be: Compared to which market, exactly?

Comparison isn’t the problem. Poor definitions are.

Comparison is not optional in professional vacation rental management.

You need it to:

- justify pricing and strategy to owners,

- prioritize where to act across a portfolio,

- understand whether a result is structural or temporary,

- decide whether a market, segment, or property is worth further investment.

Without comparison, decisions are based on intuition.

With bad comparison, decisions are based on false confidence. The issue isn’t whether you compare. It’s how you define what you’re comparing yourself against .

Why “the market” is a dangerous shortcut

“The market” sounds objective. In reality, it’s an abstraction.

Depending on how it’s defined, the same portfolio can appear:

- to outperform,

- to underperform,

- or to stagnate — all at once.

Change the definition, and suddenly:

- ADR benchmarks move,

- occupancy baselines shift,

- revenue expectations change,

- and trends look either alarming or reassuring.

This is why two managers in the same city can look at similar data and reach completely different conclusions.

The numbers didn’t change. The reference point did.

Four ways managers compare — and why each one matters

A useful comparison framework looks at the market from multiple angles, not a single lens.

1. Physical comparison: what looks comparable

This is the most intuitive layer:

- location and neighborhood,

- number of bedrooms and bathrooms,

- surface, amenities, capacity,

- property type (apartment, villa, chalet).

It answers a basic question:

Would a guest realistically consider these properties as alternatives?

This is the foundation — but on its own, it’s insufficient. Two listings can be physically similar and still live in completely different competitive realities.

2. Qualitative comparison: how the listing is perceived

This layer is often underestimated.

It includes:

- guest ratings and review volume,

- photography and design quality,

- perceived professionalism,

- consistency of experience.

From a traveler’s perspective, this is critical.

From a manager’s perspective, it explains why price alone doesn’t convert.

Comparing your results to higher-quality listings without accounting for this gap leads to one classic mistake:

“The only difference must be price.” It usually isn’t.

3. Performance comparison: separating signal from noise

Performance metrics help eliminate false competitors.

Looking at:

- occupancy,

- ADR,

- revenue levels,

- booking window behavior,

- minimum stay strategies,

allows you to filter out listings that may look comparable but clearly operate under different constraints or objectives.

This matters because copying the behavior of an outlier — without understanding why it performs that way — is how revenue leakage happens.

Price matching, in particular, is risky because:

- you don’t know the neighbor’s constraints,

- you don’t know their cash needs,

- you don’t know their historical performance,

- and you don’t know their current occupancy position.

Copying a price without context is copying an answer without seeing the question .

4. Strategic comparison: who you’re really competing with

This is where experienced operators differ from reactive ones.

Strategic comparison asks:

- Are we competing with individuals or professional managers?

- With premium inventory or volume-driven supply?

- With operators optimizing revenue or liquidity?

- With long-term players or short-term opportunists?

This lens matters when:

- setting owner expectations,

- positioning your portfolio,

- deciding whether to chase occupancy or protect rate,

- planning market expansion.

Two portfolios in the same geography may not be in the same “market” at all.

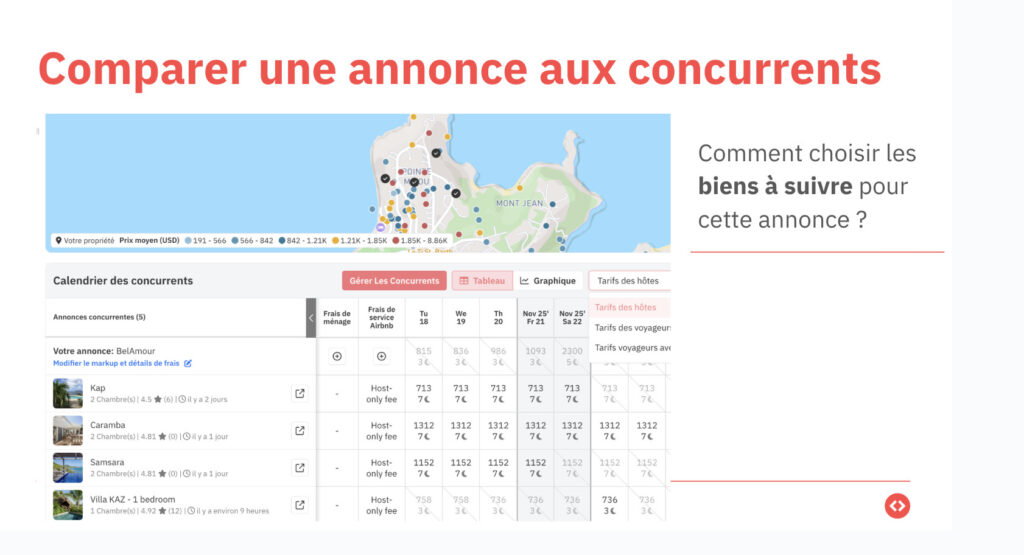

The comp set: your most misunderstood tool

A comp set is often described as:

“Nearby similar listings.”

That definition is incomplete.

A useful comp set is: The group of properties between which a traveler would genuinely hesitate.

If a traveler would never hesitate between two listings, they are not true competitors.

This applies both:

- at the individual listing level,

- and at the portfolio level.

The best operators don’t rely on a single comp set. They build multiple views of the same market.

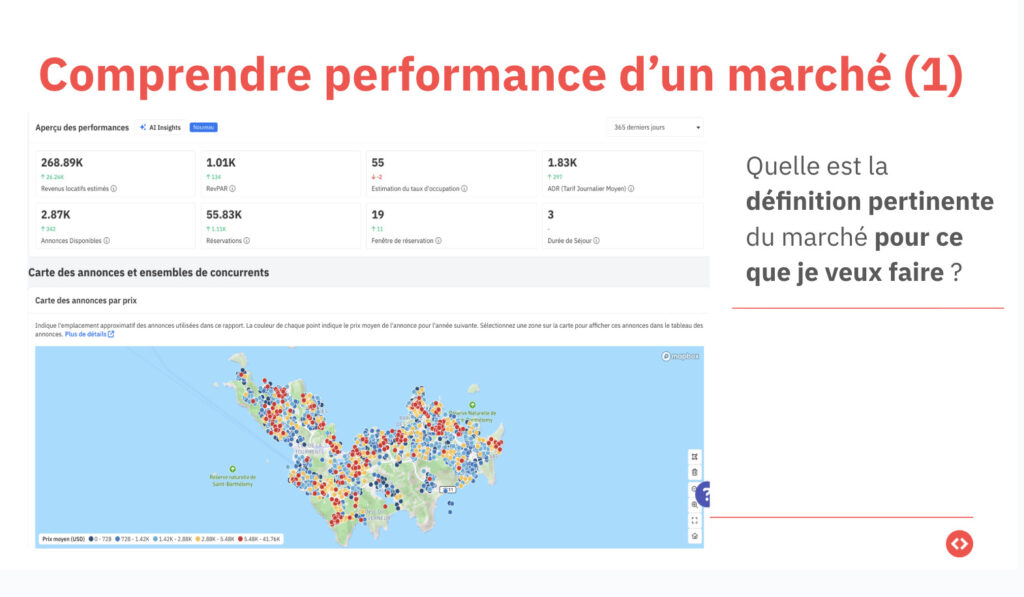

Why one market definition is never enough

When analyzing performance across a portfolio, the goal isn’t to find “neighbors.”

It’s to build reference frames, such as:

- a geographic market view (your natural supply pool),

- a quality-filtered view (only high-rated inventory),

- a professional-only view,

- a performance-based view (e.g. listings with meaningful occupancy).

Each definition answers a different question.

Using only one leads to blind spots:

- you may think you’re underperforming when you’re actually over-delivering,

- or think growth is strong when it’s driven by weaker supply entering the dataset.

Your conclusions are only as good as the lens you choose.

The real takeaway for professional managers

Strong operators don’t ask:

“How do we compare to the market?”

They ask:

“Which version of the market should we compare ourselves to — and why?”

Comparison is a strategic tool, not a vanity exercise.

Used correctly, it helps you:

- make better pricing decisions,

- prioritize listing optimization before discounting,

- explain performance clearly to owners,

- and steer your portfolio with confidence instead of noise.

Used poorly, it creates false urgency, bad pricing reflexes, and misleading internal narratives.

In short

- Comparison is essential — but only if it’s well-defined

- “The market” is not a single truth

- One portfolio needs multiple market lenses

- Good comp sets are built on substitutability, not proximity

- Clarity in comparison leads to clarity in decisions

Or simply put:

If you’re unsure whether you’re doing well, don’t question your performance first.

Question the market you’re using as a reference.

Thibault Masson is a leading expert in vacation rental revenue management and dynamic pricing strategies. As Head of Product Marketing at PriceLabs and founder of Rental Scale-Up, Thibault empowers hosts and property managers with actionable insights and data-driven solutions. With over a decade managing luxury rentals in Bali and St. Barths, he is a sought-after industry speaker and prolific content creator, making complex topics simple for global audiences.