Property managers and Revenue Managers are constantly trying to set the prices that will maximize the revenue of each property they manage. As time passes and reservations do not materialize, the pressure to discount the price starts to increase. We have all succumbed to this pressure, but possibly we shouldn’t have. It is possible we should have done the opposite. To make a data-driven decision that will help maximize your revenue, you need to know two things: Remaining Demand and Market Remaining Inventory.

Origin of the last-minute discount

A unique attribute to short-term rental nights is that they are a perishable commodity. The expiration date of the commodity (a room night) is the same as the calendar date for which the night lands. If the property does not get booked for that night, it is gone. It cannot be stored on a shelf or in a warehouse how other products can. The perishable aspect of the commodity puts a lot of pressure on the seller to price the nights accordingly. It is a well-accepted strategy for vacation homes (and hotels) that if the property is not booked, at some point, the price will start to drop. In effect, a Dutch Auction begins to take place for the property nights.

Dutch Auctions date way back to the 17th century. They operate in the opposite direction as a normal auction. In this case, the auctioneer starts at a price higher than the seller expects to receive. Then, the price decreases in increments until a bidder accepts the price. This type of auction is generally used for perishable items that need to sell quickly, and this style of auction is faster because there are no bidding wars. The first bidder is always the winner. The perishable aspect of rental nights causes revenue managers to start the last-minute discounting process, much like the auction.

Does dropping your price last minute make you more money?

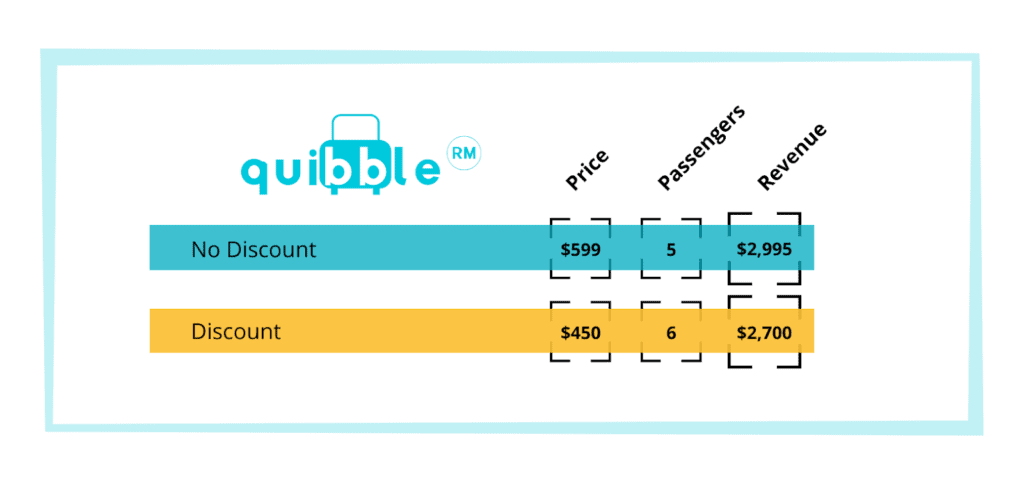

Other industries that practice revenue management do not discount the price last minute; they actually increase the price last minute. The best example of this is the airline industry. They are operating under the basic premise that travelers that book last-minute have a higher urgency to travel, which means they have a higher willingness to pay. Even when a plane has plenty of empty seats, the airline does not offer the discounted fares. They have forecast that if they offer a discount, for example, 6 passengers will book last minute and if they do not 5 passengers will book last minute. Here is an example of the revenue difference:

Short-term rentals are different in that supply is highly decentralized. In some markets, there are hundreds or even thousands of STR operators. Whereas in the airlines, it is unusual for a specific route to have more than 4 airlines operating. This makes it very unlikely that short-term rentals will have a uniform pricing strategy across all the operators. Airlines publicly file their prices, which lets their competitors know exactly what price they will charge for their last-minute customers. The STR inventory also has more diversity in the product itself (neighborhoods, bedrooms, amenities, etc.) that make the competition less comparable. These attributes of the STR market make it much harder to raise the prices last minute.

Race to the bottom

Unfortunately, what normally happens in the industry is a domino effect of cheaper and cheaper pricing. When a manager lowers their price below the market as a last-minute discount, it gives them several advantages to the comparable properties. First, they instantly become more attractive to the consumer based on the lower rate. Second, they will improve their ranking in the OTAs and be more likely to be seen and booked.

This strategy makes a lot of sense in isolation. As a manager, you can increase your booking probability with a simple price reduction. But, when the nearby competitors notice the price decrease, they will be forced to reduce their prices further in response. This is where the domino effect starts to depress the pricing, and the race to the bottom begins.

Join the race, or wait it out?

There is not a one size fits all answer to that question. There are cases where dropping your price will increase your revenue. But there are many cases where dropping your price is simply giving a discount to a guest that was willing to pay full price. There are two important things a revenue manager needs to know before deciding to drop their price: Remaining Demand and Remaining Market Inventory.

Remaining Demand

Remaining Demand is the probability you will receive a booking from this point in time until the reservation night. This is different from total demand because some of the potential days to take a reservation have already passed. The period of time we are talking about is last-minute demand, so many of the days to take a reservation have already passed. What we need to know before we offer a discount is how much demand there is left to come. Knowing the remaining demand makes you much less likely to follow your fellow managers in the race to the bottom price.

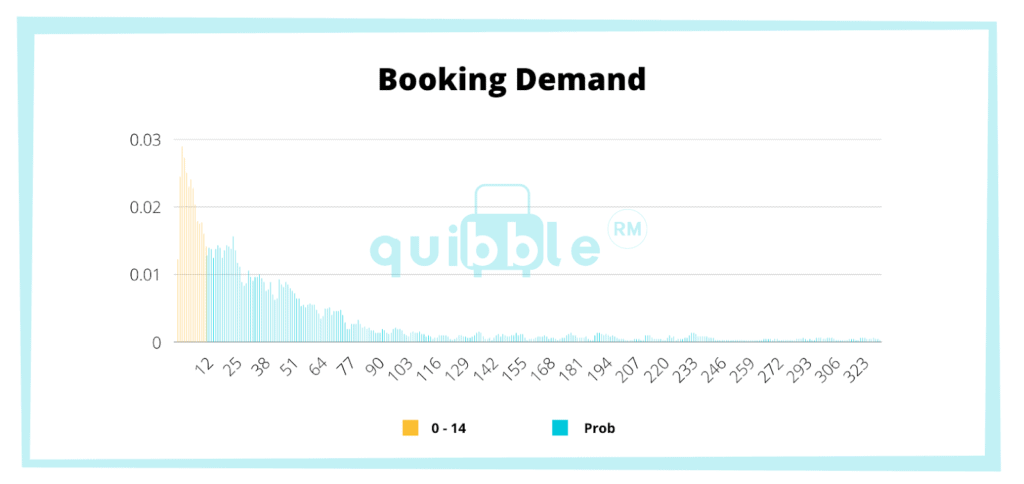

Below is an example of a Total Demand and Remaining demand:

When applying last-minute discounts, the biggest error revenue managers make is not using the remaining demand to drive the decision. In many cases, revenue managers start the price discounting with 14 days left to book. Based on certain probability curves, this can make sense. But, many times, a large portion of the bookings come within 14 days. So, the discounting starts right when the reservations are at their highest probability of happening. This is a case where you are offering a discount to a guest that would have booked at the original price. In the chart above, 0-14 days left makes up 30% of the Total Demand for the bookings. The day with the highest booking probability is 3.

As a RevPAR maximizing rule, no discounting should ever happen when there is a greater demand to come than demand in the past. In the Chart, this is on day 29. Revenue managers who do not know how much remaining demand exists tend to start discounting too early and too deeply. This negatively impacts their revenue, and the effect can reverberate to the surrounding properties when other managers start to discount in response.

Market Remaining Inventory

A secondary factor to your price discounting decision is the Remaining Market Supply of inventory. This is a secondary factor because measuring it is much less accurate than estimating the demand probability, and that is due to the challenges of collecting competitor data. But, as long as the data is within a reasonable margin, it can be very informative.

When the market has very little remaining inventory, it is not a rational time to start discounting. In many cases, the opposite is true, and it should be a signal to increase the price. The likelihood of your property getting booked is much higher when all of your competitors are already booked. Many revenue managers have automated discounting that starts to apply without taking the Market Remaining Inventory into account, which triggers discounts to apply in some undesirable circumstances.

When the market has a lot of remaining inventory, a well-executed discounting strategy will improve your RevPAR. In low-demand periods, OTA ranking becomes much more critical. In high-demand periods, revenue managers with good demand forecasts can comfortably remain low on the OTA for a period of time. This is because they know the Remaining Demand and can wait for the competitors to book first. This is less likely to happen in low-demand periods, where the total market demand could be satisfied before you rise in the search ranking.

Conclusion

Last-minute discount policies have the potential to be an asset to your revenue management strategy and can improve your RevPAR when used correctly. You can avoid the race to the lowest price by knowing your Remaining Demand. You can further improve your strategy by tracking the market Remaining Inventory. These two metrics are key to a good discounting strategy. If you need help determining your Remaining Demand or setting your strategy, Quibble can help.